Read this page in French, Portuguese, Spanish

Rece nt decades have seen rapid and sustained growth in prisoner numbers around the globe, with the result that, today, over 11 million people are in prison worldwide. Of these 11+ million, more than three million are being held in pre-trial or other form of remand detention.

nt decades have seen rapid and sustained growth in prisoner numbers around the globe, with the result that, today, over 11 million people are in prison worldwide. Of these 11+ million, more than three million are being held in pre-trial or other form of remand detention.

The causes of prison population growth are complex, but many of the consequences are clear: they include overcrowded prisons with inhumane and degrading conditions. According to their own official measures of capacity, most prison systems around the world are overcrowded – impacting mental and physical health, the safety of prisoners and staff alike, and prospects of rehabilitation. Among countries with some of the most overcrowded prisons are the Philippines (overall prison occupancy level of around 460%), Haiti (450%) and Guatemala (370%).

Over-use of imprisonment imposes enormous costs on the public purse, while disproportionately harming poor and marginalised groups in all societies. It also limits the capacity of prison systems to deal effectively with the small minority of prisoners who pose serious risks to public safety.

Prison population numbers, rates and trends in our ten countries

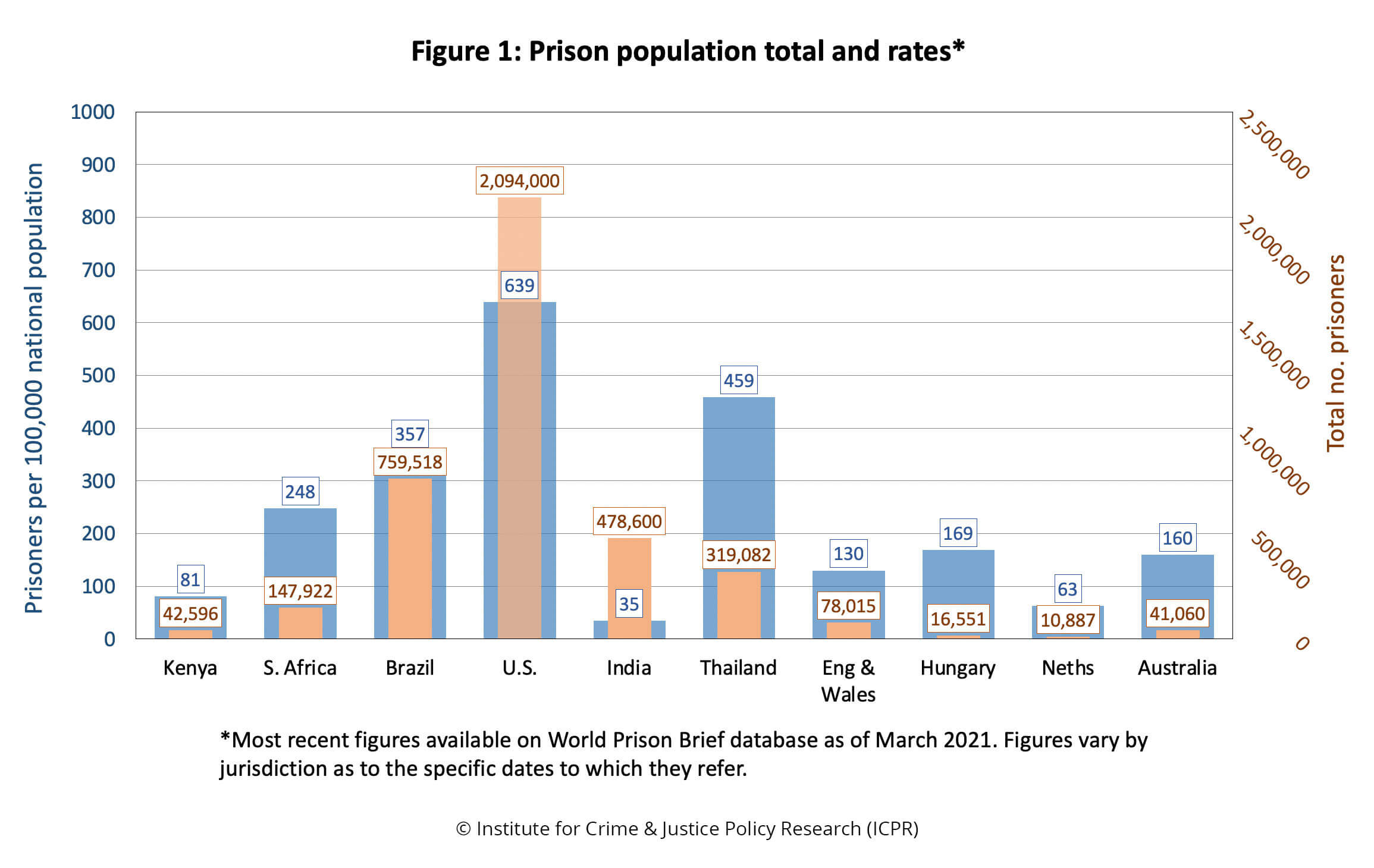

The jurisdictions in the ten-country project have widely varying prison population numbers and rates: see Figure 1. The United States’ prison population is the largest in the world at over 2 million. This equates to a prison population rate – prisoners per 100,000 of the national population – of 639: again, the highest in the world. Thailand’s prison population rate of 459, reflecting a total prison population of around 320,000, is the eighth highest worldwide; Thailand’s prisons are also severely overcrowded, with an overall occupancy level of 340%.

In contrast, India also has a large prison population total of almost half a million, but a very low prison population rate of just 35 – placing India at 209 out of the 223 jurisdictions on the World Prison Brief’s ‘highest to lowest’ ranking of prison population rates. (Another notable feature of the Indian prison population is that almost 70% of prisoners are pre-trial/remand detainees.) The prison population rates of the Netherlands and Kenya are also relatively low, at 63 and 81 respectively.

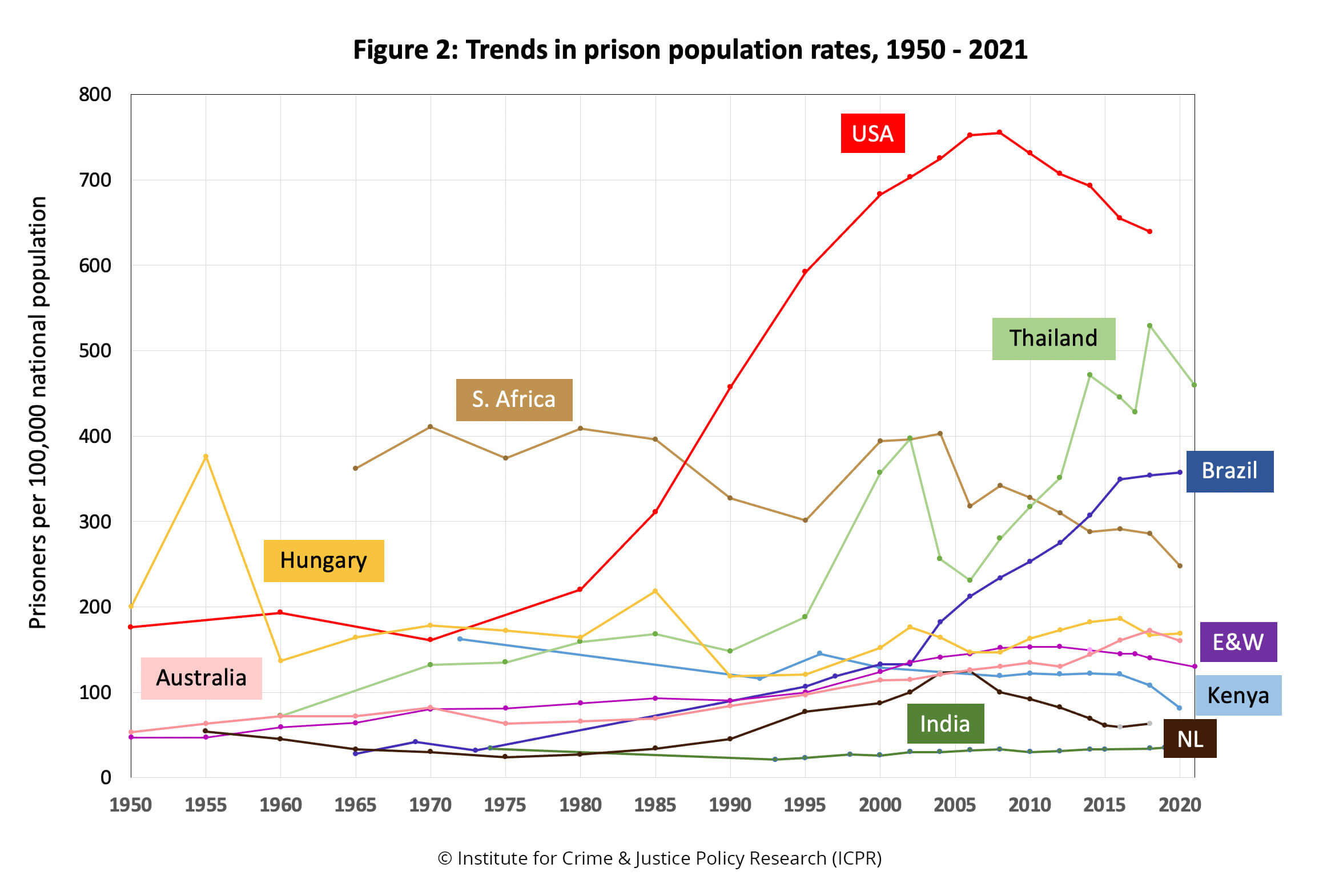

Among the ten countries are some that have seen dramatic prison population growth within the past 40 to 50 years. The size of the US prison population more than quadrupled from around half a million in 1980 to its peak of over 2.3 million in 2008, with the prison population rate increasing from 220 to 775. Brazil has seen its prison population total increase twenty-fold from around 30,000 in 1973 to more than three quarters of a million today; the rise in the prison population rate over this period was from 32 to 357.

The trend lines in Figure 2 also reveal, however, that there is nothing inevitable about prison population growth. The Netherlands saw its prison population rate increase over the 1990s and early 2000s, followed by a marked decline. The previous sharp rise in the United States’ prison population rate has also since gone into reverse, and Brazil’s surging rate appears to have plateaued.

Understanding patterns and trends in imprisonment

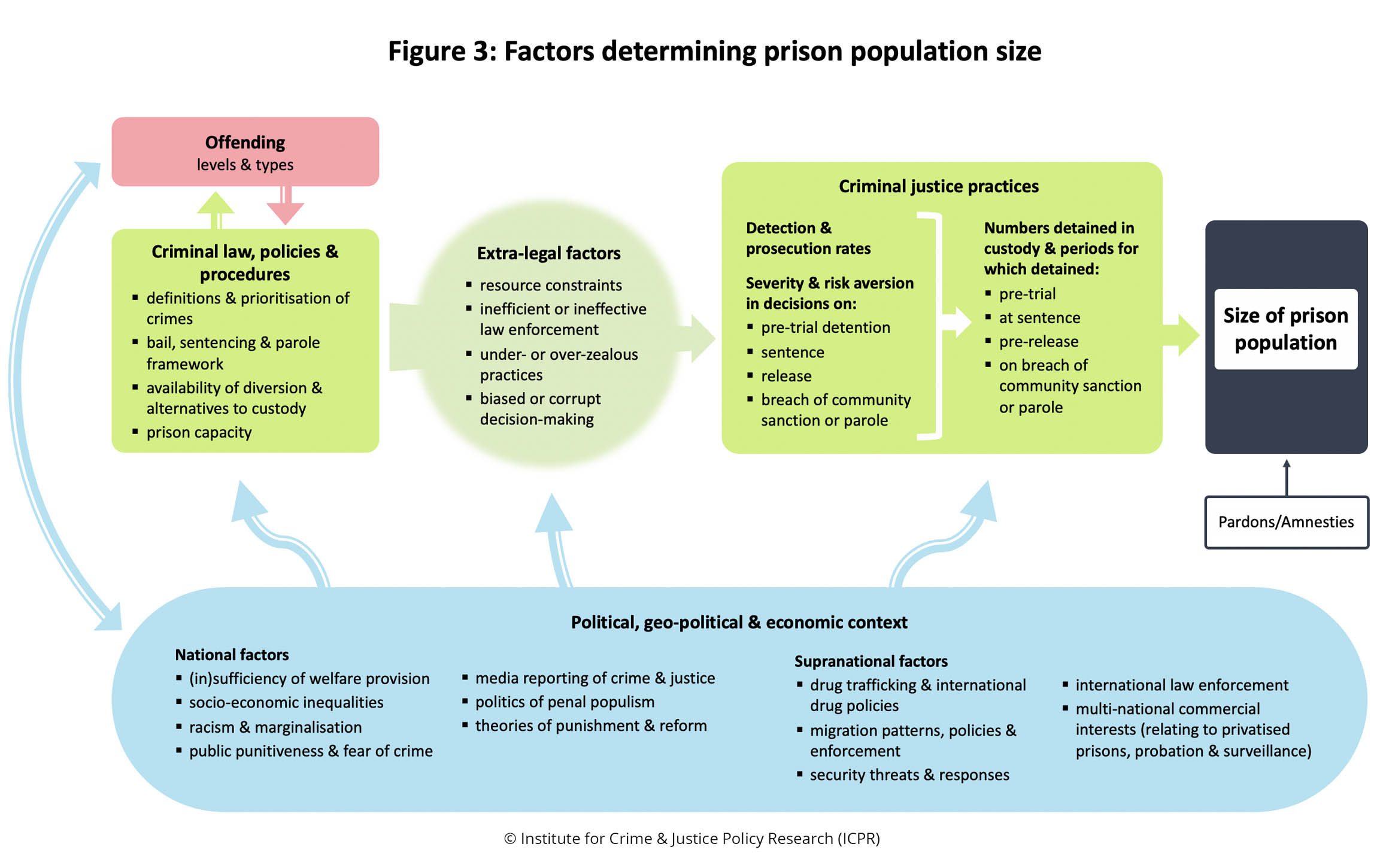

As discussed in the first published output of the ten-country project, Prison: Evidence of its use and over-use from around the world, variation in prison population rates and trends cannot be explained with reference to a single set of causes. In any given jurisdiction at any given time, the size of the prison population is determined by wide array interlocking factors, as depicted in Figure 3.

Factors which may lead to prison population growth over time include increasingly punitive public debate and political cultures; more sweeping definitions of 'criminal' behaviour; tougher enforcement; and changing patterns of crime. Such factors can conspire to increase the numbers of defendants coming before the courts, and the courts' resort to custody for those who are convicted. Higher rates of pre-trial detention are another manifestation of punitive penal policies, while also reflecting under-resourcing of, and bottle necks in, judicial processes.

While there are multiple factors that directly or indirectly promote greater use of imprisonment, so too there are moderating influences and downward pressures. In wealthy and impoverished countries alike, downward pressures include resource constraints, for the simple reason that prisons are expensive. There is growing recognition of imprisonment’s failings as a response to social problems, and that many of these problems are best tackled outside the realm of criminal justice. And whether overtly or covertly, and whether motivated by economic or other concerns, some states have made political choices to curb or reduce the use of imprisonment.

The Covid-19 pandemic has added to the pressures for penal reform and decarceration. When the pandemic was declared, some countries moved decisively to reduce prisoner numbers in order to minimise the health risks presented by overcrowded conditions. The extent to which such measures will be sustained remains to be seen.

Scope for reform

Just as there is no single explanation for the widely varying trajectories of differing countries’ use of imprisonment, there is no single route towards effective reform. But it is clear that certain cross-cutting issues must be addressed if reform efforts are to have any success. Key strategic priorities include:

- Determining the functions of imprisonment and their limits;

- Reducing the politicisation of sentencing;

- Decriminalisation of petty and ‘nuisance’ offences;

- Identifying and tackling disproportionate treatment of marginalised groups in pre-trial and sentence decision-making;

- Drug policy reform, encompassing decriminalisation and harm reduction;

- Ensuring pre-trial detention is used only as a last resort, and for the shortest periods possible;

- Addressing the public health consequences of over-use of imprisonment.

Read the report and recommendations.